The Clockwork Rocket, which is the first volume in Greg Egan’s brand new hard science fiction trilogy Orthogonal, is a book with three different but equally important focal points. On the one hand, it’s the story of a young woman who also happens to be a very alien alien. On the other, it’s a novel about a planet—a very alien planet—on the cusp of tremendous social change. And, maybe most of all, it’s a book about a universe with, well, alien laws of physics. Greg Egan successfully weaves these three threads into one fascinating story, but be warned: if you don’t like your SF on the hard side, The Clockwork Rocket may be a tough ride for you. Hard as it may be, it’s worth sticking with it, though.

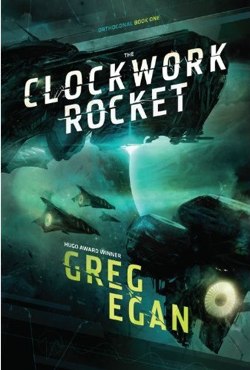

The Clockwork Rocket‘s cover blurb is a perfect way to introduce the book, so I’m going to go ahead and quote part of it here:

In Yalda’s universe, light has no universal speed and its creation generates energy.

In Yalda’s universe, plants make food by emitting their own light into the night sky.

As a child, Yalda witnesses one of a series of strange meteors, the Hurtlers, that is entering the planetary system at an immense, unprecedented speed. It becomes apparent that her world is in imminent danger—and that the task of dealing with the Hurtlers will require knowledge and technology far beyond anything her civilization has yet achieved.

So yes, Yalda’s the focus, the universe is the focus, and the planet she lives on (and the fact that it’s in danger) is the focus too.

Yalda is The Clockwork Rocket‘s fascinating protagonist. When we first meet her, she’s a young girl living and working on her family’s farm, but it quickly becomes apparent that she’s smarter than average, so she ends up going to school, later to a university, and eventually will become a respected physicist involved in the attempt to save her world from the Hurtlers.

Yalda’s species is one of the most alien ones I’ve encountered in SF. They are able to reshape their bodies, e.g. by extruding extra limbs as needed. This also allows them to “write” on their skin by forming symbol-shaped ridges. They have two sets of eyes, front and back. But most fascinating is the way they reproduce: the female effectively divides into four children (usually two male-female pairs of “co’s”) and dies in the process, leaving the male to raise the children.

Greg Egan does great things, extrapolating an entire society from this starting point. The idea of “reproductive freedom” takes on a whole new meaning when the female is guaranteed to die when giving birth. Some females refuse this fate and run away, but even then there’s a chance that they might spontaneously conceive, so there’s also a black market for an illegal contraceptive drug and a network of independent women to support it. This obviously threatens to move the planet towards something like gender equality, so Yalda’s world, which technologically seems to be at roughly the same level as ours in the first half of the 20th century, is also going through some of that period’s political and societal changes.

And then there’s the universe. Greg Egan takes his very alien aliens and then places them in a universe that’s ruled by different physical laws than ours. The fact that light doesn’t have a universal speed is just one of them. He explains, at great length and with a multitude of accompanying diagrams, exactly how different it is, what those differences mean, and how they apply to the story. This often happens in the form of pages-long lecture-dialogues between two scientists. There is a lot of science in this novel—so much that it may turn off some readers. Random example from p. 94:

“The geometry gives us that, easily,” Yalda replied. “For a simple wave, the sum of the squares of the frequencies in all four dimensions equals a constant. But we also know that the wave’s second rate of change in each direction will be the original wave multiplied by a negative factor proportional to the frequency squared.”

Another one, from p. 304:

“The second mystery,” Yalda continued, “is the structure of particles of gas. There are plenty of symmetrical polyhedrons where putting a luxagen at every vertex gives you a mechanically stable configuration—which seems to make them good candidates for the little balls of matter of which we expect a gas to be comprised. But those polyhedrons share the problem solids have: the luxagens rolling in their energy valleys will always have some low frequency components to their motion, so they ought to give off light and blow the whole structure apart.”

Now, a book reviewer who complains about science in a Greg Egan novel is just about as silly as a music reviewer who complains that a Metallica album has too many loud guitars in it. It’s basically par for the course. However, it’s also fair to warn people who haven’t read much Greg Egan yet that they’ll encounter quite a lot of paragraphs like the ones above. Pages full of them, actually.

So, your reading experience with The Clockwork Rocket is going to be very different depending on how hard you like your science fiction and how much you appreciate an author who doesn’t just wave his hands and shout “Hocus Pocus FTL Drive!” Greg Egan really integrates his science into his story, to the point where the novel wouldn’t make sense without it. When he shows Yalda discovering that universe’s equivalent of the Theory of Relativity, it’s both scientifically impressive and highly relevant to the story. But at the same time, I’m a humble liberal arts major who already knows that he’ll have trouble helping his children with their high school math homework, and for people like me, some of the endless scientific explanations in this book are frankly tough sledding.

If you want more information about the background of The Clockwork Rocket‘s universe, Greg Egan helpfully provides it on his website, both in a version for people with only high school trigonometry, algebra and calculus and one for people who have undergraduate level physics and mathematics under their belt. If your eyes glaze over reading the basic version, your experience reading this novel may be similar to mine: I truly admire this novel, but I can’t honestly say that I enjoyed every single page of it.

Nevertheless, I’m still eager to read the rest of the Orthogonal trilogy, because Greg Egan achieves something very few SF novels manage: he creates some real, old-fashioned sensawunda. Just the concept of the clockwork generation starship would be enough to keep me coming back for more, not to mention the curiosity about what will happen when the descendants of Yalda’s crew—no doubt evolved towards vastly different social norms—return to their home planet. And as alien as the characters are, Greg Egan manages to make you empathize with them and sometimes even forget they’re not human, which is quite an achievement.

The Clockwork Rocket is probably the hardest hard science fiction novel I’ve ever read, but it also has a surprising amount of heart. For Greg Egan fans, and fans of hard SF in general, the Orthogonal trilogy will be a real treat. For people who come to SF more for the fiction than the science, it may be a more challenging read—but ultimately a rewarding one. Bring on book two.

Stefan Raets reads and reviews science fiction and fantasy whenever he isn’t distracted by less important things like eating and sleeping. Many of his reviews can be found at Fantasy Literature.